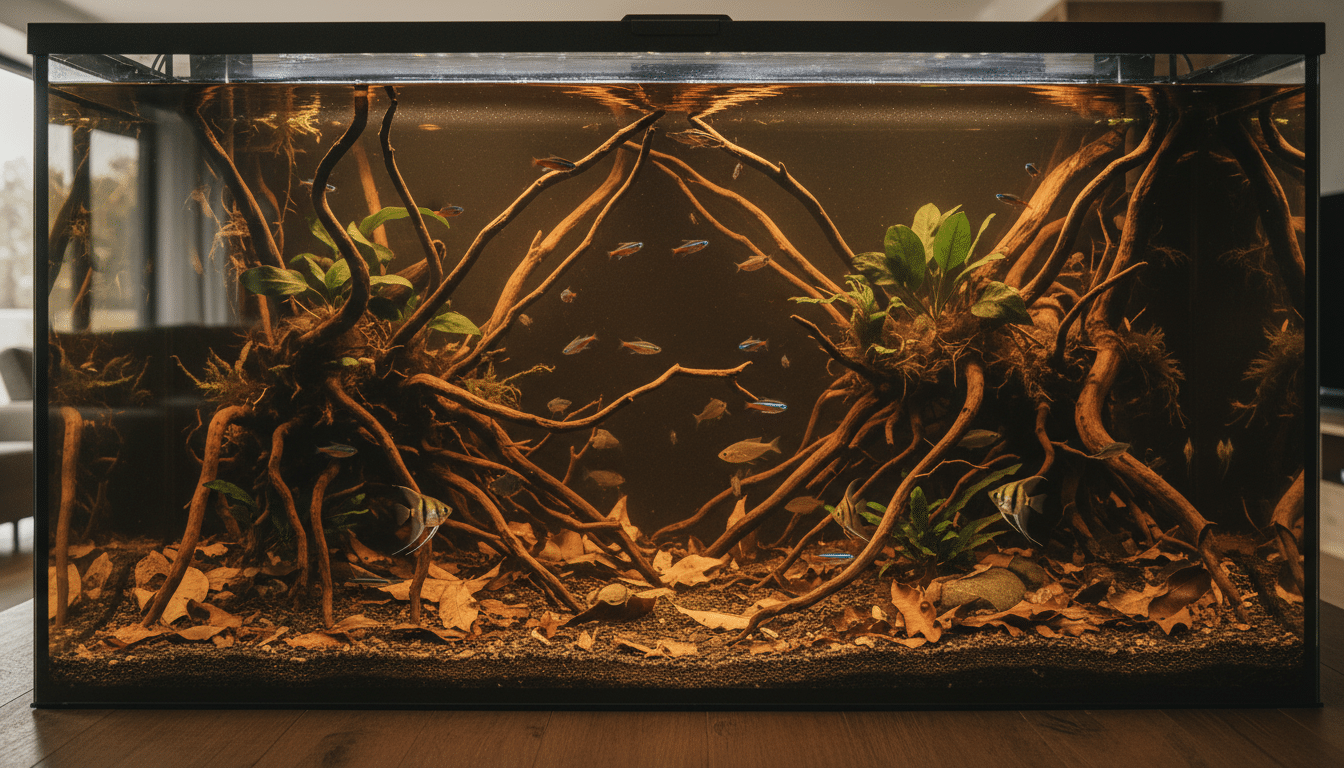

Ever wondered why some fish tanks look like they’ve been dipped in tea? That’s the magic of a blackwater fish tank, and trust me, once you understand what’s happening beneath that amber surface, you’ll see why so many fish absolutely love it.

A blackwater tank mimics the natural conditions of rivers like the Amazon, Rio Negro, and waterways across Southeast Asia. These environments are stained dark brown by tannins released from decaying leaves, wood, and organic matter. The water looks like strong tea, but it’s actually creating a perfect home for species that evolved in these conditions over millions of years.

What Makes Blackwater Different From Your Typical Tank

The distinctive color is just the surface story. Blackwater aquariums have unique chemistry that fundamentally changes how fish interact with their environment. The pH typically sits between 4.0 and 6.5, which sounds extreme if you’re used to neutral tanks, but it’s home sweet home for many tropical species.

Here’s something most people don’t realize: the tannins in blackwater actually provide antibacterial and antifungal properties. This is why fish from these environments often have fewer disease issues when kept in properly maintained blackwater conditions. The tannins create a protective barrier that helps prevent infections, particularly important during spawning or when fish are stressed.

The water is also incredibly soft, often measuring below 3 dGH (degrees of general hardness). Combined with low electrical conductivity, this creates an environment where certain species breed more readily. Ever notice how some fish just won’t spawn in regular tap water? Chances are they’re waiting for conditions that remind them of home.

Which Fish Actually Need Blackwater Conditions

Not every fish benefits from blackwater, so let’s get specific about who really appreciates it. Wild bettas (not the fancy pet store varieties) come from blackwater streams and show much better coloration in these conditions. We’re talking about species like Betta rutilans or Betta uberis that most people have never heard of.

Discus are the poster children of blackwater fish, and for good reason. These cichlids from the Rio Negro basin show deeper reds and more intense patterns when kept in water that mimics their natural habitat. Temperature should sit around 28-30°C (82-86°F) for these beauties, which is warmer than most community tanks.

Cardinal tetras and rummy nose tetras display colors you’ve probably never seen in a regular tank when they’re swimming in proper blackwater. The same goes for many small catfish species like Corydoras from South American watersheds. Their barbels stay healthier in the softer, more acidic water.

Here’s an interesting observation: Chocolate gouramis, those notoriously difficult fish that seem to die if you look at them wrong, become surprisingly manageable in blackwater conditions. The pH around 5.0 and temperatures of 25-28°C (77-82°F) suddenly make them look like they belong in a beginner’s tank.

The Southeast Asian Connection

It’s not just South American fish that love blackwater. Many rasboras, particularly species like the harlequin rasbora or the stunning Boraras species, come from peat swamp forests in Malaysia and Indonesia. These habitats can have pH levels as low as 3.0 in the wild, though you don’t need to go quite that extreme in your tank.

Asian arowanas and many snakehead species also originate from blackwater environments. Even certain loaches prefer the gentler chemistry that tannins provide.

Creating Your Own Blackwater Environment

Setting up a blackwater tank isn’t about dumbing tea bags in your filter (please don’t do that). The most effective method uses natural materials that slowly release tannins while also providing other benefits.

Indian almond leaves (Catappa leaves) are the go-to choice for most people. Drop a few leaves into your tank and watch them gradually turn the water amber over several days. One leaf per 38 litres (10 gallons) is a good starting point, though you can adjust based on how dark you want the water and what pH you’re targeting.

Driftwood, particularly Malaysian driftwood and mopani wood, releases tannins consistently over months. Bonus: it looks fantastic and provides hiding spots. The wood will leach tannins more heavily at first, so don’t panic if your water turns the color of cola within 48 hours.

You can also use alder cones, which look like tiny pinecones and pack a serious tannin punch relative to their size. Three to five cones per 38 litres (10 gallons) will gradually acidify your water while encouraging biofilm growth that many fry and shrimp love to graze on.

The Setup Process That Actually Works

Start with RO (reverse osmosis) water or very soft tap water if you’re lucky enough to have it. Hard tap water fights against everything you’re trying to achieve, and you’ll burn through botanical materials trying to overcome the buffering capacity of those minerals.

Add your substrate first. Sand or fine gravel works better than crushed coral or limestone-based substrates, which will constantly push your pH upward. Some people use aquasoils designed for planted tanks, which also help lower pH naturally.

Place your driftwood and arrange it before filling the tank. Once you add water and botanicals, visibility drops fast. Fill the tank about halfway, add your Indian almond leaves or alder cones, then complete the fill. The water might look shockingly dark at first, but it will settle to a more translucent amber color.

Here’s the critical part most guides skip: don’t add fish immediately. Let the botanicals work for at least a week while you monitor pH daily. Blackwater chemistry can shift quickly, especially in smaller tanks. A 75-litre (20-gallon) tank stabilizes much more easily than a 40-litre (10-gallon) setup.

Maintaining Water Chemistry Without Going Crazy

The pH in a blackwater tank can be surprisingly stable once established, but you need to understand what you’re working with. Those tannins create what’s called organic buffering, which is different from the carbonate buffering in regular tanks.

Test your water every few days initially. You’re looking for pH to settle somewhere between 4.5 and 6.0 for most species. If it’s not dropping enough, add more botanical material. If it’s dropping too fast (rare but possible in very soft water), slow down on the leaves and cones.

Water changes require a bit more thought. You can’t just dump in regular tap water without shocking your fish. Prepare your replacement water in advance by treating it with botanicals or using commercial blackwater extracts. Some folks keep a dedicated bucket with leaves steeping constantly for water changes.

How often should you change water? This is where blackwater tanks surprise people. You can often get away with smaller, more frequent changes rather than the typical 25-30% weekly routine. Something like 10-15% twice a week works well because it maintains chemistry more consistently while removing accumulated organic waste.

The Filtration Equation

Here’s where things get interesting: traditional chemical filtration removes tannins. Those carbon cartridges everyone loves? They’ll strip the color right out of your carefully crafted blackwater. Remove activated carbon entirely from your filter setup.

Stick with mechanical and biological filtration only. Sponge filters work beautifully in blackwater tanks, and they won’t demolish the tannins you’ve worked to establish. Canister filters are fine too, just skip the carbon media.

The flow rate matters more than you’d think. Many blackwater species come from slow-moving streams or still waters. Aim for gentle circulation rather than the whitewater rapids some filters create. Your fish shouldn’t be fighting current constantly.

Plants and Blackwater: The Complicated Relationship

Can you grow plants in a blackwater tank? Absolutely, but you need to choose wisely. The reduced light penetration means high-light carpet plants will struggle or fail completely.

Cryptocoryne species are the obvious winners here. These plants actually come from similar environments in Southeast Asia and handle low light beautifully. Cryptocoryne wendtii, Cryptocoryne spiralis, and Cryptocoryne parva all do well in blackwater conditions.

Java fern and Anubias are no-brainers. These slow-growing plants tolerate low light and actually seem to show better growth in softer water. Attach them to your driftwood for a natural look that matches the biotope perfectly.

Here’s something worth knowing: many floating plants like Amazon frogbit or red root floaters actually help filter the water while thriving in these conditions. They’re getting light from above anyway, so the stained water below doesn’t bother them.

Stem plants are trickier. Most need more light than penetrates deeply stained water. If you really want them, keep the water lighter (use fewer botanicals) or upgrade your lighting significantly.

Common Mistakes That Tank Your Success

The biggest error people make is trying to maintain blackwater conditions in tiny tanks. A 20-litre (5-gallon) blackwater tank is an exercise in frustration. The chemistry swings wildly, and you’ll spend more time testing and adjusting than enjoying your fish. Start with at least 75 litres (20 gallons) for your first blackwater attempt.

Another classic mistake: mixing incompatible species just because they’re all “tropical.” Mollies and guppies hate blackwater. They evolved in hard, alkaline waters and will suffer in the soft, acidic conditions your tetras love. Research the natural habitat of every species you’re considering.

Don’t expect crystal-clear visibility. That’s not the goal here. If you’re someone who needs to see every fish perfectly at all times, blackwater might not be your style. Embrace the mysterious, shadowy aesthetic where fish dart in and out of view.

Overfeeding becomes more problematic in blackwater tanks because decomposing food accelerates pH drops and increases organic load. Feed conservatively and watch how quickly food disappears. If anything’s still sitting on the bottom after five minutes, you fed too much.

The Breeding Advantage Nobody Talks About

Want to know a secret? Many difficult-to-breed species suddenly become prolific in proper blackwater conditions. The soft, acidic water makes eggs more permeable during fertilization, which improves spawn success rates dramatically.

Apistogramma cichlids are perfect examples. These dwarf cichlids spawn regularly in blackwater setups, whereas they might ignore each other completely in neutral water. The pH around 5.5 combined with temperatures of 26-28°C (79-82°F) triggers breeding behavior that’s hardwired into their genetics.

Even notorious egg-eaters like certain tetras show more parental restraint in blackwater. The tannins reduce light penetration, which seems to calm fish down and reduce the stress that leads to egg predation.

When Blackwater Isn’t the Answer

Let’s be real for a moment: not everyone should set up a blackwater tank. If you love African cichlids from Lake Malawi or Lake Tanganyika, forget it. These fish need hard, alkaline water and will absolutely hate blackwater conditions.

Goldfish, livebearers, and most North American natives don’t belong in blackwater either. Know what your fish actually need rather than forcing them into conditions that look cool but cause stress.

If you’re keeping a mixed community tank with species from different continents and water types, neutral conditions with minimal tannins make more sense than going full blackwater. Not every tank needs to be a biotope.

Living With the Amber Glow

Once your blackwater tank is established and running smoothly, you’ll notice things you never saw in regular tanks. Colors pop differently against the dark background. Fish behave more naturally when they’re not constantly exposed in crystal-clear water. Watching rams or apistos defend territory through drifting leaves hits different than seeing the same behavior in a bare, bright tank.

The maintenance rhythm becomes second nature. Keep botanicals on hand and replace leaves as they break down completely, usually every three to four weeks. Monitor pH weekly once things stabilize, then monthly when you’re confident in your routine.

You’ll probably find yourself staring at the tank more than you expected. There’s something mesmerizing about the filtered light and shadowy movements. It’s less like watching a display and more like peeking into an actual stream in the Amazon or a Malaysian peat swamp.

Creating a blackwater tank means committing to a different kind of fish keeping. It requires more initial research and slightly more attention to chemistry, but the payoff is fish that look and act like their wild counterparts. That amber water isn’t just aesthetic, it’s functional habitat that brings out the best in species that evolved to live in it.