Let me be straight with you: fish tank snails aren’t inherently bad. They’re more like that friend who’s incredibly helpful 90% of the time but can occasionally crash on your couch for way too long. Whether snails become a problem in your aquarium depends entirely on the species you’re dealing with and how you manage your tank.

The real question isn’t whether aquarium snails are villains or heroes. It’s about understanding what they do, recognizing when they’re helping versus hurting, and knowing how to keep them in check. Think of this as your complete guide to the complex relationship between you and these shelled tank inhabitants.

The Good Side: Why Many People Actually Want Snails

Here’s something that might surprise you: plenty of people deliberately add snails to their aquariums. Why? Because the right snails act like your tank’s cleanup crew, working around the clock without asking for overtime pay.

Nerite snails, for example, are absolute algae-eating machines. They’ll scrape algae off your glass, decorations, and plants without touching the healthy plant tissue itself. A single nerite can consume remarkable amounts of algae, keeping your viewing panes crystal clear. Even better, they can’t reproduce in freshwater, which means you’ll never wake up to a surprise snail population explosion.

Mystery snails and Malaysian trumpet snails serve different but equally valuable roles. Mystery snails eat leftover fish food and decaying plant matter, preventing these materials from fouling your water. Malaysian trumpet snails burrow through your substrate, aerating it and preventing anaerobic pockets where harmful bacteria love to set up shop. It’s like having a tiny maintenance team living in your gravel.

The Biological Filtration You Didn’t Know You Had

Here’s an interesting fact most people overlook: snails contribute to your tank’s nitrogen cycle. As they digest organic waste, they produce ammonia that beneficial bacteria convert into less harmful compounds. They’re literally part of your biological filtration system, processing waste that would otherwise accumulate and create water quality issues.

When Snails Become a Problem

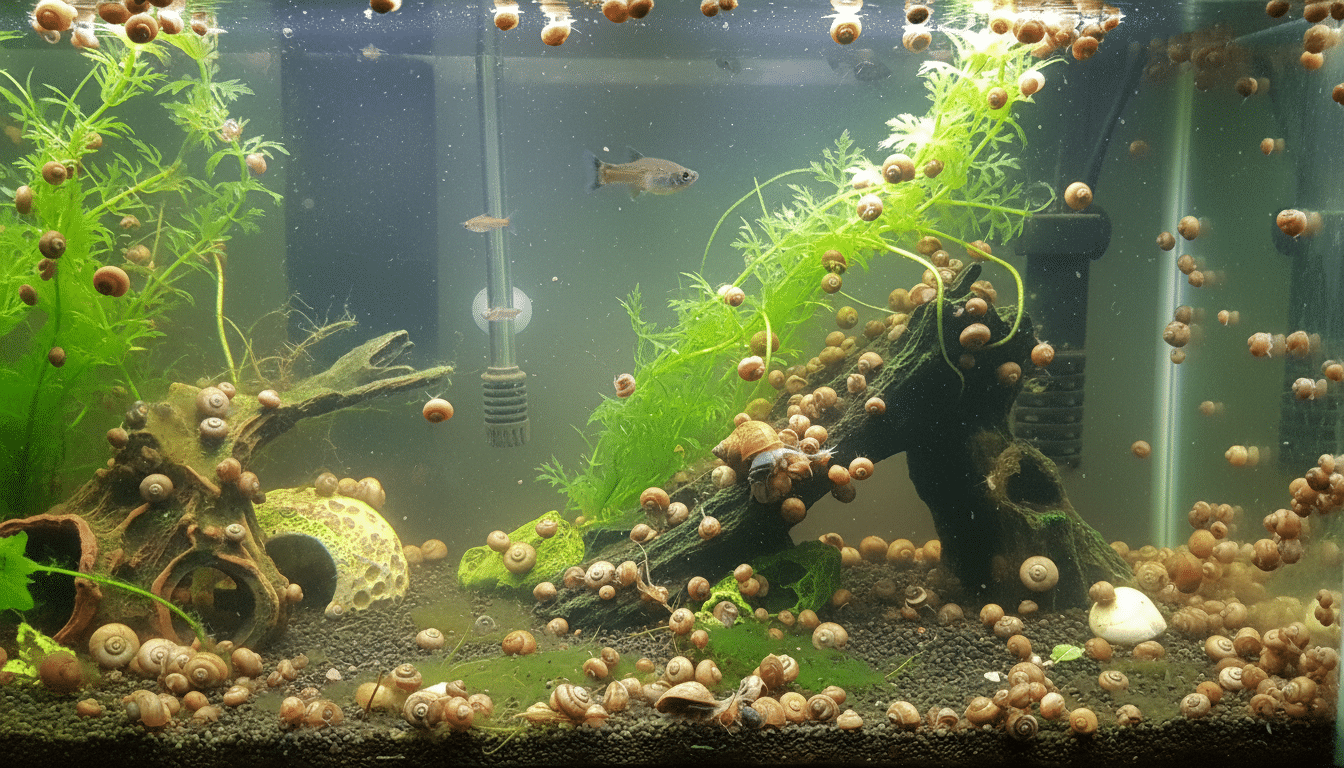

Now let’s talk about the dark side. Certain snail species can multiply faster than you can say “population explosion,” and that’s when people start viewing them as pests rather than pets.

Bladder snails, pond snails, and ramshorn snails are the usual suspects. These species are hermaphroditic, meaning a single snail can potentially reproduce on its own. They lay gelatinous egg clusters that can contain dozens of eggs, and in optimal conditions, they’ll breed prolifically. We’re talking about going from three snails to three hundred in a matter of weeks.

The problem isn’t really the snails themselves. It’s what their overpopulation signals: you’re overfeeding your fish. Snails need food to reproduce rapidly, and if there’s enough leftover fish food and decaying matter to support a massive snail colony, you’ve got excess nutrients creating other problems too. Higher nitrate levels, algae blooms, and murky water often accompany snail infestations.

Can Snails Actually Harm Your Fish?

This is where we need to separate fact from fiction. Healthy snails won’t attack or harm healthy fish. However, some species like assassin snails will eat other snails (that’s literally their job). And in extremely rare cases, snails might nibble on a sick or dying fish, but they’re scavengers, not predators. They’re cleaning up what was already lost, not causing the problem.

The bigger issue is competition for resources. A massive snail population can deplete oxygen levels at night when they’re all respiring, potentially stressing fish in heavily stocked or poorly aerated tanks. They also consume calcium from the water to build their shells, which can affect water chemistry if your tank is particularly snail-heavy.

Snails and Your Live Plants: Friend or Foe?

This question keeps coming up in forums, and the answer is surprisingly nuanced. Most aquarium snails won’t touch healthy plants. What they will eat are dying or dead leaves, algae growing on leaves, and biofilm covering plant surfaces.

But there are exceptions. Apple snails (a type of mystery snail) have been known to munch on certain soft-leaved plants when hungry or if their preferred food is scarce. If you’re seeing holes in your plants, check what you’re feeding and whether your snails have enough alternatives. A well-fed snail in a tank with plenty of algae and detritus has no reason to bother your prized Amazon swords.

Here’s a clever trick: snails often congregate on dying plant matter before you even notice the plant is declining. They’re like an early warning system for plant health issues. If you see multiple snails clustering on one plant, inspect it closely for rot or deficiencies.

How Snails Get Into Your Tank (When You Didn’t Put Them There)

Ever wonder how snails magically appear in a tank where you never added any? They’re hitchhikers, and they’re surprisingly good at it. Snail eggs attach to live plants, decorations, and equipment from other tanks. Those tiny gelatinous blobs you might not even notice can introduce an entire snail population.

Even fish store plants that look perfectly clean can harbor microscopic eggs or juvenile snails smaller than a grain of sand. Within weeks of adding new plants, you might spot tiny spiral shells cruising across your glass. This is why many people quarantine new plants in a separate container with a saltwater dip or a quick rinse in aquarium-safe solutions before adding them to their main tank.

Managing Snail Populations Without Going Nuclear

Let’s say you’ve got more snails than you bargained for. Before you tear apart your entire aquarium, try these practical approaches that actually work.

First, address the root cause: reduce feeding. If your fish finish their food within two to three minutes, you’re feeding the right amount. Anything left over becomes snail food. Cut back slightly, and watch the snail population gradually decline over the next few weeks as food becomes scarce.

Manual removal is tedious but effective. Drop a piece of blanched vegetable (zucchini or lettuce) into your tank before bed. By morning, it’ll be covered in snails that you can simply lift out and dispose of. Do this every few days, and you’ll significantly reduce numbers without chemicals or drastic measures.

Natural Predators That Actually Help

Introducing assassin snails is like hiring a specialized pest control service. These carnivorous snails actively hunt and eat other snails, and they reproduce much more slowly than pest species. A few assassins in a moderately infested tank can restore balance within a couple of months.

Certain fish species also eat snails, though results vary. Loaches (particularly clown loaches and yoyo loaches) are famous snail predators, crunching through shells with ease. Pea puffers are even more voracious, but they require specific water parameters around 24 to 26°C (75 to 79°F) and can be aggressive toward other tank mates. Make sure any snail-eating fish you add is compatible with your existing setup.

The Chemical Route: When and Why to Avoid It

You’ll find chemical snail treatments at most pet stores, but here’s my honest take: they’re rarely worth the risk. These products kill snails effectively, but then you’re left with potentially dozens or hundreds of dead snails decomposing in your tank simultaneously.

This sudden die-off releases ammonia and other compounds into the water, potentially triggering a mini cycle or ammonia spike that can harm or kill your fish. The cure becomes worse than the disease. Plus, copper-based treatments (common in snail killers) can harm invertebrates like shrimp and remain in your substrate for months, making it difficult to keep sensitive species later.

If you’re dealing with a truly overwhelming infestation, your better bet is manually removing as many snails as possible, then using the feeding reduction method to prevent new generations from establishing.

Species Spotlight: Know Your Snails

Not all snails are created equal, and identifying what you’re dealing with makes all the difference. Bladder snails have thin, amber-colored shells that spiral to the left, while pond snails have brown shells spiraling to the right. Both reproduce rapidly and are considered pests by most people.

Ramshorn snails come in various colors from red to brown to blue, with flat, coiled shells. They multiply quickly but are easier to spot and remove than bladder snails. Malaysian trumpet snails have cone-shaped shells and are nocturnal, burrowing in substrate during the day.

On the “desirable” end, nerite snails have beautifully patterned shells and won’t breed in freshwater. Mystery snails grow quite large (up to 5 cm or 2 inches) with smooth, rounded shells. Assassin snails have distinctive yellow and brown striped shells and, as mentioned, eat other snails.

Temperature and Water Parameters Matter

Here’s something worth knowing: snail reproduction rates are heavily influenced by temperature. Warmer water speeds up their metabolism and breeding cycle. If you’re keeping tropical fish at 26 to 28°C (79 to 82°F), expect snails to reproduce more rapidly than in cooler tanks.

Water hardness also plays a role. Snails need calcium carbonate to build shells, so they struggle in very soft water. If you have naturally soft water with low mineral content, snail populations may grow more slowly, and their shells might appear thin or pitted. While this might sound like a benefit if you’re fighting snails, it indicates water chemistry that might need adjustment for other tank inhabitants too.

Making Peace With Snails

After keeping aquariums for years, I’ve come to view snails as neutral inhabitants rather than good or bad. They’re indicators, really. A few snails in your tank? You’ve got a balanced ecosystem. An explosion of hundreds? Something’s off with your feeding routine or maintenance schedule.

Some of the healthiest, most stable tanks I’ve seen have modest snail populations quietly doing their job. The glass stays cleaner, the substrate stays aerated, and decaying matter disappears quickly. These aren’t problems; they’re solutions with shells.

The key is maintaining control rather than attempting elimination. A dozen snails in a 75-litre (20-gallon) tank isn’t a crisis. It’s a cleanup crew. But three hundred snails means you’re providing resources for three hundred snails, and that excess needs addressing.

Final Thoughts on Your Shelled Tank Mates

So are fish tank snails bad? It depends entirely on your perspective, the species involved, and your tank management. They’re extraordinary algae eaters, diligent cleaners, and fascinating creatures to observe. They’re also capable of reproducing faster than almost any other tank inhabitant if conditions are right.

Rather than viewing snails as enemies or allies, think of them as feedback. They’re telling you something about your tank’s nutrient levels, feeding schedule, and overall balance. Listen to what they’re saying, adjust accordingly, and you’ll find that coexisting with a reasonable snail population is not only possible but potentially beneficial.

The tanks I’ve enjoyed most weren’t sterile environments devoid of snails. They were balanced ecosystems where every organism, including those humble snails, played a role in maintaining stability. That’s not just good tank keeping. That’s understanding how aquatic environments actually work.